"I Worked on That Building": My First Contribution to Firefox

firefox opensource engineering

This is the first entry in a short series of bite-sized blogs where I share my experience contributing to Mozilla’s open-source Firefox browser.

A Familiar Kind of Pride

Many of my family members and friends work in construction. One thing I’ve always found funny — but also deeply endearing — is how, whenever we drive past a building they helped build, they immediately call it out: “I worked on that building!” There’s pride in their voice. And rightfully so. They helped make something real — something visible and accessible to the public.

Recently, I started contributing to Firefox, and for the first time, I felt that same kind of pride. “I worked on that building.”

Getting Set Up with Firefox

Contributing to a project as massive as Firefox is no small thing. It’s one of the largest and most complex open-source codebases out there.

The first step in the process was setting up my local development environment so I could run and test a local build of Firefox. That meant creating accounts for Bugzilla, Phabricator, and SearchFox, and downloading the entire Firefox codebase — around 31 million lines of code — to my machine.

Firefox still uses Mercurial instead of Git (though they’re currently transitioning into Git), which added an extra learning curve. But once everything was configured, I was able to launch Nightly, a special development version of Firefox. It looks just like the browser we all use — except it has a blue globe icon. This local version lets me test changes, experiment, and, eventually, fix bugs.

Finding My First Bug

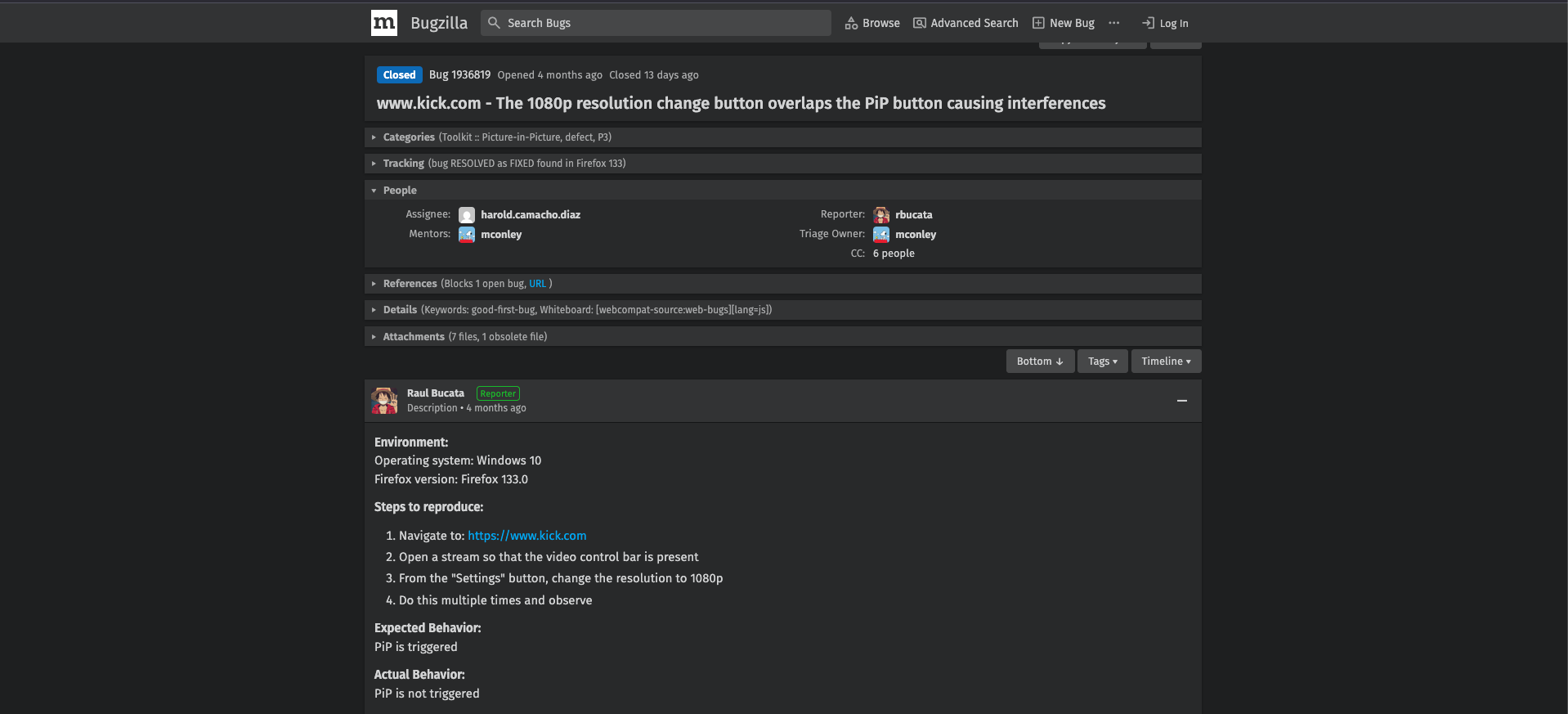

With my setup ready, it was time to go bug hunting. Mozilla uses a platform called Bugzilla to track issues. That’s where I found my first one: on kick.com, the resolution menu was overlapping the picture-in-picture button. If you clicked on the menu, it would accidentally trigger picture-in-picture mode.

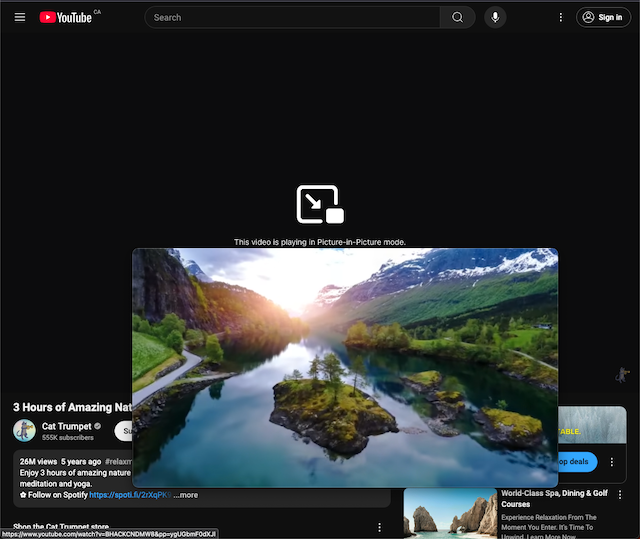

Picture-in-Picture (PiP) is a browser feature that lets you pop out a video into a small, floating window.

A Mozilla engineer had left a comment on the bug suggesting: “We might need to add an override and set the visibilityThreshold to a slightly different value on kick.com.”

Unless you’ve worked on Firefox before, that might sound like a line from a sci-fi movie. But it was a clue — and I decided to follow it.

Diving into Documentation and Code

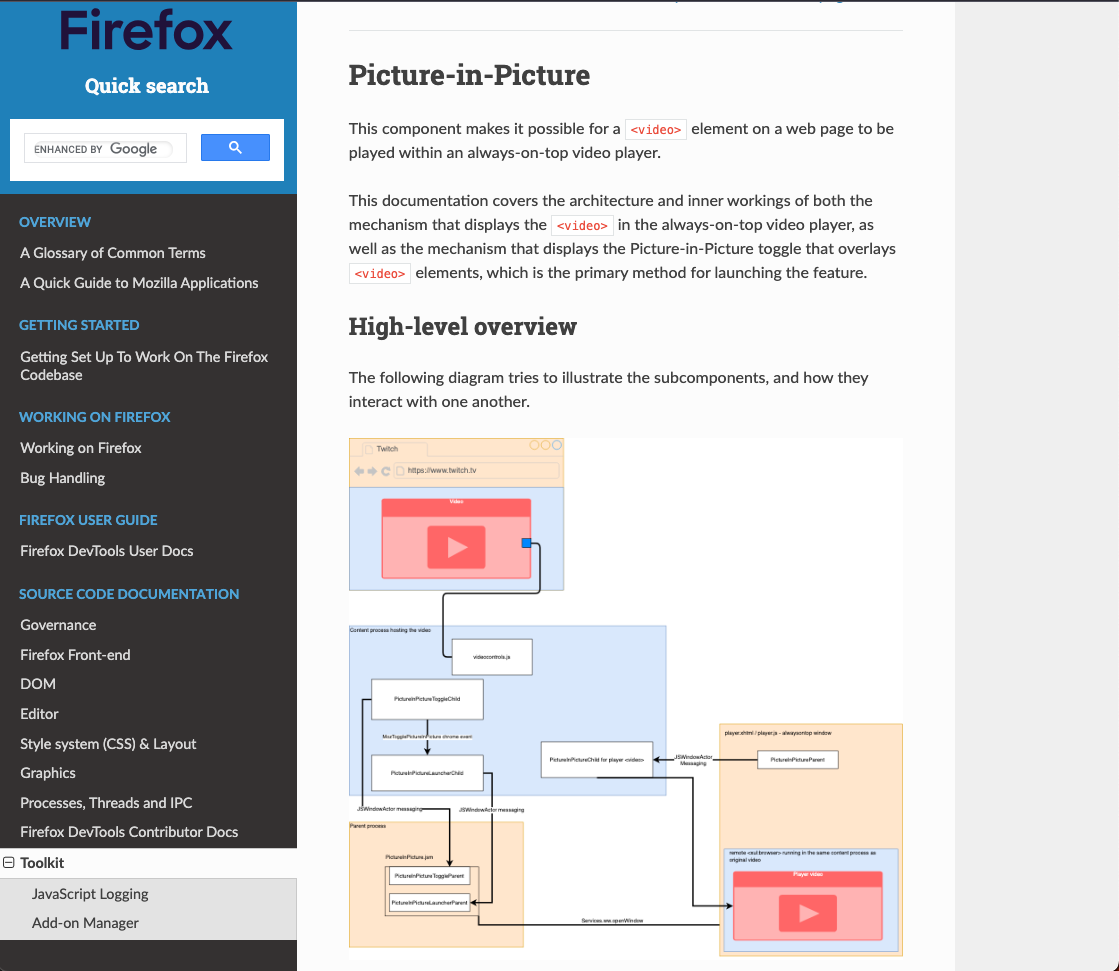

Before jumping into the code, I turned to Mozilla’s source documentation, which turned out to be a lifeline. Since the bug was related to the picture-in-picture feature, I spent some time reading everything I could about how that component works, which files define it, and how it interacts with other parts of the browser.

The docs pointed me to files like PictureInPicture and PictureInPictureChild, so I started diving into the code. But after a while, I realized I’d gone too deep without making real progress. So I zoomed back out and kept reading.

That’s when I discovered something called Site-Specific Video Wrappers.

Aha Moment: Site-Specific Overrides

These wrappers allow Firefox to customize picture-in-picture behavior for specific sites — enabling subtitles, fixing layout quirks, and resolving playback inconsistencies. They’re defined in a file called picture_in_picture_overrides.

Suddenly, the engineer’s comment made total sense.

I checked the overrides file. Kick.com wasn’t listed, so I added a new entry and set the visibilityThreshold value. I built the browser, ran it — and… nothing. I tried a few more values. Still nothing…

Asking for Help

Feeling stuck, I reached out to the Mozilla engineer who had left the original comment and shared my work-in-progress patch on Phabricator, a collaborative code review tool used by Mozilla.

He reviewed my changes — everything looked correct. So he brought in another engineer, and the two of them started troubleshooting together. Eventually, they traced the issue all the way down to the display list visibility hit-test code — a part of the browser’s rendering pipeline.

They patched the backend code, and I had to pull in that new patch, rebase my changes on top of it, do a full build, and confirm that everything now worked as expected on kick.com.

Once I verified the fix, I moved my patch out of work-in-progress status and submitted it for formal review. The reviewer approved it, and eventually, my patch was successfully landed. Just like that, my contribution came to life.

Small Fix, Big Learning

My final patch? Just a few lines of JavaScript. But understanding the bug’s context, navigating this massive codebase, and collaborating with Mozilla engineers — that’s where the real learning happened.

This small fix was packed with lessons. I learned how important it is to stay focused on the immediate context of the bug rather than getting lost in rabbit holes — something that can happen fast in systems this complex. I also learned how valuable clear, timely communication is when working with a distributed team.

And most importantly, I learned how to find the right place to make a change. In a 31-million-line codebase, knowing where to write those few lines of code is the real task.

In the end, it wasn’t just about writing code. It was about breaking down the problem, taking deliberate steps to understand it, and collaborating effectively with others to ship a real fix.

Final Thoughts

That override I added? It’s now part of Firefox. I can open the browser, point to that change, and say: “I worked on that building.”

This was just the first bug I tackled — more stories to come. If you made it this far, thank you for reading!

Also, the full bug report is available here for anyone interested in checking it out.

Until next time!